- Last Cast Letter

- Posts

- Last Cast Letter #33: The Digital Paradox

Last Cast Letter #33: The Digital Paradox

Why an Online World Is Driving an Offline Future

Hi All - Happy Wednesday. It’s the last day of the month (and last day of the year!), which means it’s time for the Last Cast Letter.

I need to make a confession.

I do something that I despise every day. In fact, it’s the first thing I do before I even get out of bed.

I roll over and reach for my phone. I take it off “do not disturb,” and immediately, I’m bombarded by a stream of notifications.

On a scale of “stressed” to “not stressed”, this flood of information (a lot of it useless) definitely “stresses me out” more than it calms me down.

Even though I recognize an increased feeling of anxiety tied to looking at the device, for some reason, I can’t. not. look.

Throughout the day, I find myself reaching for my phone, just to reach for it.

It’s wild!

I’m not the only one who does this, and I’m not the only one who feels this way.

I, like many of you, am a digital crackhead, addicted to my phone, pulling down to refresh the feed like a gambling addict waiting for the next dopamine hit.

Vivid description, and probably a bit dramatic, but still pretty spot on. I tell you this for a few reasons:

I’m going to work on this in the new year. When you say and write things to yourself and others, there’s more accountability. So if you see me in public doing the fent-lean over my phone, help me snap out of it. (My other New Year’s Resolution is to dress better.)

Use this mini anecdote, which, again, is something that I bet a lot of us do, to tee up this month’s thought piece. Because, to my point above, the reality is that you probably WON’T see me in public, which is another structural part of our society that I think begs some consideration.

To the example above, and as you know, we live in a world that feels increasingly digital, remote, and perfectly optimized.

Tasks we once did in person (shopping, banking, socializing, even dating) are now largely mediated by screens. As mentioned, my phone is constantly buzzing. At what point does convenience stop feeling like progress?

There is a deeper tension here. I feel it when I reach for the phone in the morning. I’m sure you feel it as well.

Sure, technology has made certain parts of life easier. But ease does not equate to meaning. We are connected in data streams yet disconnected in our daily lived experience.

That contradiction is the core of what I call the digital paradox. If life keeps moving online, where do humans move toward?

My working hypothesis, borne of both observation and evidence, is this: the more virtual life becomes, the more valuable real, shared, physical experiences become.

If this thesis is correct, where can we allocate capital and invest to benefit from this trend? I have a few thoughts.

Let’s dig in.

Part 1: A Few Stats to Frame Our Rapidly Digitizing World

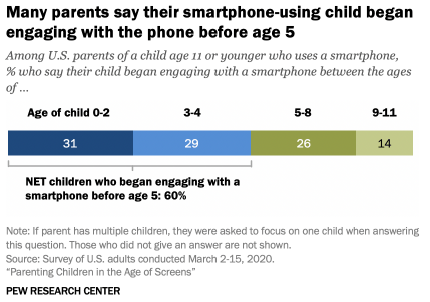

Digital Adoption Is Happening Earlier Than Ever

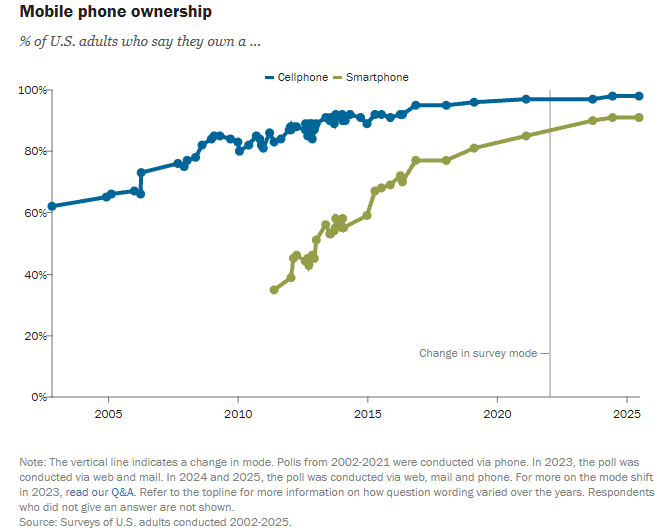

Every generation today is born into a digital ecosystem. Smartphones, once disruptive novelties, are now nearly universal:

From Pew Research: “The vast majority of Americans – 98% – now own a cellphone of some kind. About nine-in-ten (91%) own a smartphone, up from just 35% in the Center’s first survey of smartphone ownership conducted in 2011.”

We’re exposed to them earlier than ever:

To that end, for younger cohorts, screens are the environment they know.

As of 2025, Gen Z averages around 9 hours of screen time daily (Source) and American adults as a whole report more than 7 hours per day on screens. In fact, check out this stat from Deloitte:

“Over 104 million working age Americans spend more than seven hours daily viewing digital screens, leading to health consequences ranging from digital eye strain (DES) or computer vision syndrome (CVS) to headaches, back and neck pain. When these symptoms are unmanaged, they cost an estimated $151 billion to the U.S. health system, worker productivity and wellbeing in 2023.”

Work Has Gone Remote, Asynchronous, and Disembodied

Remote work peaked as a necessity during COVID, but it has stuck because both employers and employees now see it as normal. Yes, there has been a push for return to office, but remote/hybrid work is absolutely more acceptable than it was when I graduated from college.

Recent data shows that 75% of employees whose jobs can be done remotely are working from home at least part of the time. (Pew Research Center)

At a practical level, this means fewer water-cooler conversations and more Slack threads. Work is efficient in many ways, but it is also dislocated from place and shared physical rhythms. It is no longer a space you go to: it is just what you do from anywhere.

That autonomy is a sort of freedom, but it comes with psychological costs.

Surveys consistently report that remote workers struggle with loneliness, lack of in-person mentorship, and a sense of isolation.

From Fortune: “Remote workers reported the highest levels of anger (25%), sadness (30%), and loneliness (27%) compared to hybrid and on-site workers.”

That is significant. Work is more than income. It is structure, community, identity, and purpose. More on this later.

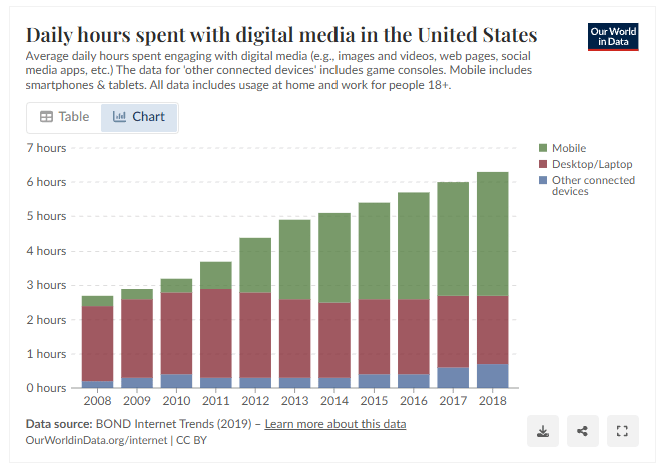

We Are Online… A Lot

I mean, just look at the chart below from Our World in Data:

For perspective, six hours per day is more time than most of us spend eating, commuting, or exercising.

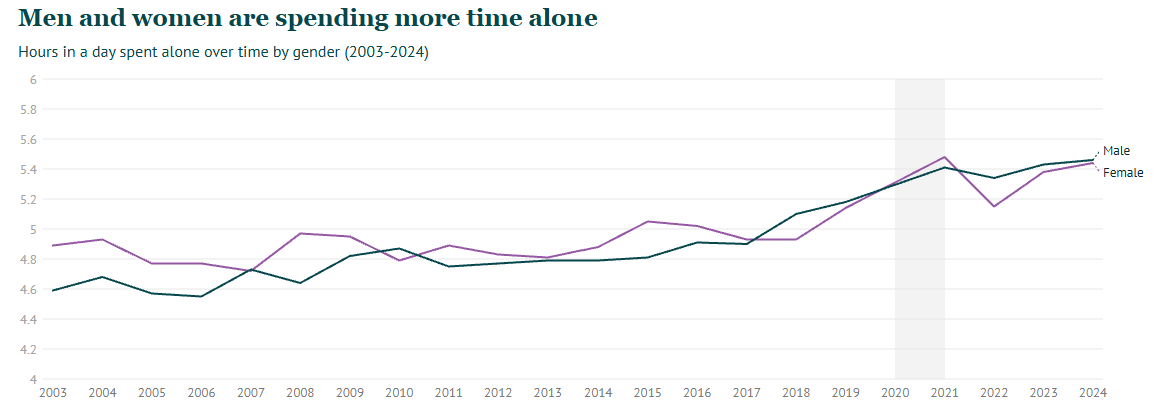

The Loneliness Data

The above is making people feel isolated.

Loneliness is often framed as an elderly problem. That is not accurate.

Recent research shows that people of all ages report rising levels of loneliness, and it is increasingly common among working-age adults. And especially, US males.

A 2025 AARP survey found 40% of Americans 45 and older reported loneliness, up from 35% in prior years. (The Washington Post)

AI as an Accelerator (Not the Cause)

Make no mistake: AI is accelerating these trends.

Tools like ChatGPT, large language models, and automation platforms compress tasks we used to do in person or with more time into digital interactions. That efficiency is real and valuable. But it does not by itself produce meaning.

In the same way email improved communication but could not replace human rapport, AI scales information and productivity, but it does not scale belonging.

AI, as we all know, will bring both good and bad. I want to pull at some of those strings below.

Part 2: Productivity, Free Time, and the Uneasy Future of Work

The Productivity Argument

Optimists point to the promise of AI and automation to enhance productivity.

CEOs and other “thinkers” talk about shorter workweeks, higher outputs with fewer hours, and a world where humans are liberated from menial tasks.

In theory, this is compelling.

If machines can handle optimization and repetitive work, humans could reallocate time to creative, meaningful pursuits.

The Other Side: Fear, Displacement, Uncertainty

But reality is uneven.

As roles automate, fewer people are needed for the same output in certain industries.

That translates into job insecurity, career disruption, and extended periods between meaningful work.

If work takes less time, or if large swaths of jobs disappear—or even if hybrid roles cut out daily social interaction—then this raises a central question:

What fills the void? Where does purpose come from when traditional work ceases to provide it?

Many visionaries, including Elon Musk, have posited a future where automation and robotics could make work optional for many people.

Whether or not you agree with that vision, it forces us to confront the human dimension of work beyond economics.

Those arguments stir debate, but they point to a broader philosophical point: when humans are liberated from necessity, they still need purpose.

The Underrated Role of Work

Even imperfect jobs offer structure, deadlines, social networks, and identity.

More importantly, in my opinion, work is more than income; it is rhythm, status, and community, and purpose.

Purpose is so, so important here, I can’t stress this enough.

The idea of “work” or “going to work” is often paired with negative emotions. We get “Sunday Scaries” because the weekends were so fun, and we dread going to work on Mondays, so we get scared on Sundays. I get it.

But life would be absolutely horrible if it were one infinite weekend. Saturdays and Sundays wouldn’t be so special. Everything would blend together and become meaningless.

Every man needs a mission.

Without work as an anchor, people will start seeking meaning elsewhere.

More specifically, I think humans will put a premium on raw, unfiltered, in-real-life, authentic experiences. This is where they will derive purpose, especially set against a background that is increasingly the opposite (digital, perfect, remote, curated).

“Real-world” experiences include the following:

Live events that create collective memory

Travel that embeds humans in place and culture

Sports and performance where embodiment matters

Physical communities that generate spontaneous interaction

Part 3: We’re Seeing Some Pushback Already

Younger Generations Are Moderating Digital Use

Ironically, generations steeped in digital life are increasingly opting for balance.

Many teens and young adults are experimenting with digital detoxes, reducing social media time, or adopting "dumb phones" to escape screen saturation.

“Have you ever noticed that devices and screens aren’t usually in your dreams?” Airbnb’s CEO, Brian Chesky, makes a really interesting observation below:

Even digital natives crave control and presence.

Nostalgia for a Pre-Digital Era

Popular culture reflects this, too.

Hit shows like “Stranger Things” tap into an 80s / 90s aesthetic, not because the past was perfect, but because that era symbolizes real connection, outdoor play, and unmediated experience.

This nostalgia for the past is driving fashion trends:

Part 4: If This Thesis Is Right, Where Does Capital Flow?

For argument's sake, let’s say I’m right.

In this hypothetical world, let’s also say you walked into a 7-11, bought a lottery ticket, and won $1 million.

As you’re leaving, the homeless man standing outside puts you in a headlock and forces you to tell him where you’re going to allocate your winnings. This is what you might tell him:

Live, In-Person Experiences as Scarce Assets

Abundance in the digital realm creates scarcity in the physical one.

I know the crypto/blockchain community is trying to solve this, but many digital items can be copied infinitely.

A live, in-person experience cannot.

A building on a plot of land on an island cannot.

That scarcity creates value.

Let’s start with live events, and let’s focus on a publicly traded company.

Live Nation (LYV) is interesting to me. It’s the world's largest live entertainment company, producing, marketing, and selling live music events, including concerts and festivals, while also owning venues and managing artists through divisions like Ticketmaster, House of Blues, and Artist Nation.

If there is anything Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour taught us, it is that people will spend money (sometimes money they don’t have) on live events. Swift’s Eras tour became the first tour to gross over $2 billion in ticket sales alone.

According to the US Travel Association, the tour drove $5-10 BILLION (Yes, Billion!) of spending on the US economy. Look at this specific stat:

Denver’s two concerts resulted in visitor spending that contributed an estimated $140 million to the state’s GDP.

Like, wtf? That’s insane!

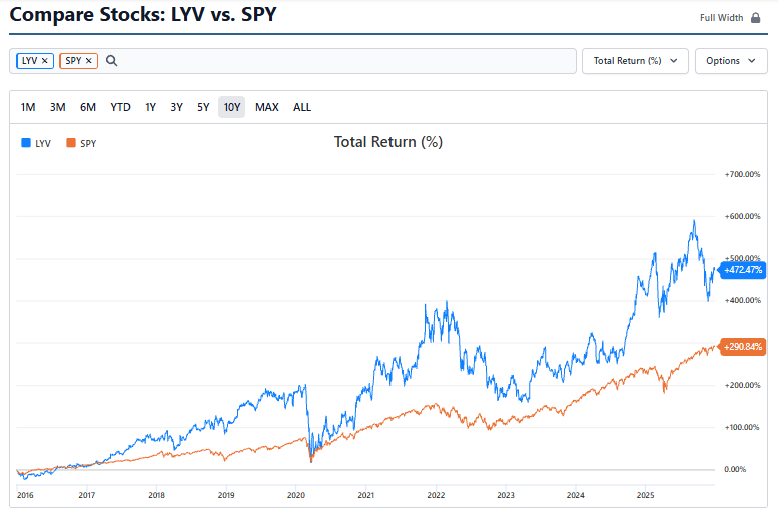

$LYV ( ▼ 3.96% ) has outperfomed the $SPY ( ▼ 0.57% ) over the past 10 years (chart below). Past performance is never a guarantee of future results, but there’s an argument to be made that this trend might continue:

Go Deeper With this Video:

Hard Assets In Places That People Want to Hang Out

Now, imagine that the homeless guy who has you in a headlock doesn’t like that answer.

He got burned by Live Nation because even though it’s outperformed the broad index over the past 10 years, it’s underperformed the index over the past 12 months.

You tell him you have some thoughts about real estate.

Not so much in terms of specific asset classes, but rather geographies that could do well over the next 5-10 years if this thesis holds.

As remote work loosens the tie between job location and home address, people can increasingly choose where to live based on lifestyle, community, and experiences rather than just where their employer is.

The winners in that world are not the cheapest or the most “efficient” buildings, but neighborhoods and projects that are experiential: walkable blocks, activated ground floors, curated amenities, and events that build a local scene.

Bigger Markets

Miami is a biased example from my own life, but it fits the thesis well. The city offers year‑round outdoor living, dense social energy, and a strong event calendar (Art Basel, major sports events, crypto and tech conferences) that pull people into the city and then keep them around. During and after COVID, Miami became a magnet for remote workers and founders who realized they could work over Zoom and spend the rest of their time outside, away from their screens.

Beyond Miami, there are a handful of markets that fit the same structural profile if this thesis is right.

Austin and Nashville stand out as culture-first cities in no-income-tax states where music, events, and social density pull people out of their homes and into shared spaces.

Tampa and St. Petersburg benefit from Florida’s tax structure and migration trends while layering in waterfront, arts, and sports driven experiences that are hard to replicate digitally.

On the Mountain West side, places like Boise and Sun Valley attract residents less for jobs than for lifestyle, outdoor community, and a sense of presence that screens cannot replace.

In Texas, Dallas-Fort Worth’s outer ring cities are growing fast as people trade pure affordability for community, space, and family-oriented living, even as infrastructure and zoning lag demand.

Phoenix and Scottsdale offer a similar dynamic, pairing Sun Belt growth with sports, events, and an outdoor social calendar that anchors people physically.

None of these markets is immune to cycles, but they share a common thread: people are choosing them, not being assigned to them.

Other “Escape” Markets

At a smaller scale, there are also resort and “escape” markets that quietly benefit from the same forces.

Places like Jackson Hole, Park City, and Sun Valley are physically constrained by geography and zoning, which limits new supply while demand is driven by lifestyle rather than employment.

In the Southeast, towns like 30A, Seaside, and parts of the Florida Keys function as social ecosystems built around shared outdoor experiences.

Mountain towns such as Telluride, Steamboat Springs, and Whitefish attract residents who are opting into place, not commuting to it.

Coastal enclaves like Charleston’s barrier islands or Hilton Head operate similarly, blending community, recreation, and repeat visitation.

These markets are seasonal by nature, but that seasonality is part of their appeal, creating rhythms that feel human rather than optimized. Capital tends to flow to them not because they are cheap, but because they are scarce.

In a digital world, these places sell presence, not productivity.

(The homeless guy liked that answer; he thought it was well thought-out)

See You Next Year

So there you have it, my 2700-word novel to end the year.

At the risk of oversimplifying it, I think we are heading toward a world where efficiency keeps rising, but meaning does not automatically come with it. Screens will get better, AI will get faster, and work will become more flexible, but humans will still crave purpose, rhythm, and connection.

When traditional anchors like offices, commutes, and shared routines fade, people will look for substitutes that feel real. That search, in my view, leads directly to places, events, and communities that force you to show up in person.

Capital tends to follow behavior, and behavior is already shifting toward experiences that cannot be refreshed, copied, or automated. This does not mean technology loses; it just means it stops being the whole story. In a digital-first world, the edge belongs to what remains stubbornly analog.

And if you ask me where the next decade quietly rewards patient investors, I would start with wherever people still want to be, together, without a screen in between them.

If you're thinking about how to put capital to work and want to talk about what we’re seeing across our deals and operations, I’d love to connect.

Click the button below and fill out our form.

— Brooks